From ChatGPT to Court Sanctions: Why Public AI Tools Are Professional Malpractice Waiting to Happen

Your Client, Your Signature, Your Problem: A Guide to the Legal AI Minefield

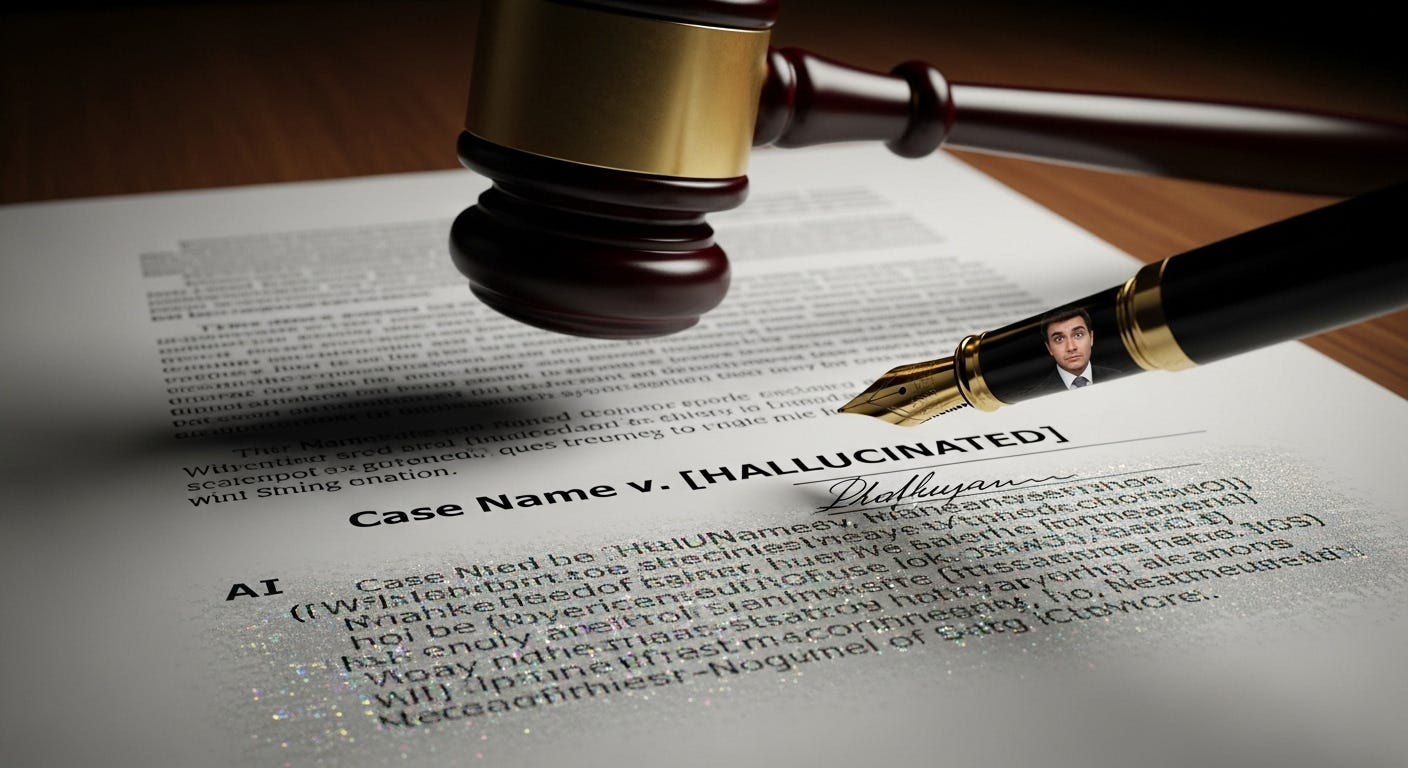

Anyone who follows the legal tech world has read about Mata v. Avianca. But it's worth taking a moment to consider the human element of that story. Imagine a lawyer having to stand before a federal judge and explain why a brief bearing their name was filled with fictitious case law. The professional fallout from that event was a stark warning for the entire legal industry: a powerful new tool, used improperly, can lead to a fundamental failure of professional responsibility.

For practicing lawyers, this isn't a theoretical risk management exercise. It's a direct threat to your licenses and reputations. AI is an undeniably powerful tool for efficiency, but its rapid adoption has been met with a chaotic and frankly confusing patchwork of court rules. The duty of technological competence has a new, high-stakes dimension, and navigating it requires a level of clarity that has been hard to find.

So let’s cut through the noise. The most critical distinction I advise firms to build their policies around is the difference between the two kinds of AI.

The Two AIs: One is a Liability, The Other is a Tool

There is a bright, uncrossable line here. Using consumer chatbots (the free, public versions of tools like ChatGPT or Claude) for substantive client work with model-training or data-sharing enabled should be treated as a confidentiality violation absent informed client consent or a confidentiality agreement that bars provider access and use. Default settings on popular consumer tools often allow training/retention unless you opt out; treat public tools as non-confidential. If you must experiment, strip out client identifiers and sensitive strategy - or better yet, don’t use consumer tools for client matters at all.

The only professionally responsible way to integrate this technology is through secure, enterprise-grade platforms (or tightly controlled API/on-prem deployments). These come with contractual guarantees that a firm’s data is private, encrypted, and will not be used to train public models.

Adopting a secure tool is the baseline - not the finish line. It shifts the risk from a high likelihood of confidentiality exposure in consumer tools to a more familiar mix of vendor security and professional judgment. Even with enterprise tools, you still have unsettled questions around privilege and work-product, and the practical reality that prompts and outputs may be treated as business records. In other words: assume your team’s prompts and outputs are potentially discoverable and subject to preservation when a legal hold is in place.

With that distinction made, here is how two key jurisdictions - California and New York - are approaching regulation. I’ve researched the legal AI guidelines now in all 50 states, but want to highlight these two to start in order to share some learnings.

California: The Decentralized Mandate

In California, the Judicial Council has directed courts to adopt their own AI use policies for judges and staff. There isn’t a single statewide practice rule you can rely on for filings. The standing order for one judge in the Northern District of California may require you to identify AI-drafted text and retain prompt records, while a court in San Diego may be silent. The burden is squarely on counsel to check local rules and individual judges’ standing orders every time.

Example: In N.D. Cal., Magistrate Judge Peter H. Kang requires filers to identify portions drafted with AI and to maintain prompt records. Treat that as a preview of where many courts may land: disclosure, verification, and retention.

New York: The Signature-Certification (Part 130) Approach

New York - home of the Avianca debacle - is leaning into what every litigator lives by: the signer’s certification. The Commercial Division’s proposed Rule 6(e) doesn’t fixate on the tool; it focuses on the act of certification under New York’s Part 130 (a state analogue to Federal Rule 11). The rule requires filers to verify any information obtained from AI and to certify accuracy. The message is simple: AI is an assistant, not a source. The lawyer who signs is personally attesting to the accuracy of every word, no matter how it was drafted. That aligns with existing professional obligations and treats AI-generated text the way a partner treats a cite pulled by a first-year: you don’t trust; you verify.

A Defensible AI Policy for Your Firm

The landscape is a mess of individual orders and evolving guidance. But the core principles of professional responsibility have not changed. Law firms need a clear, defensible policy that every person understands. In my work with clients, the policies that hold up share three pillars:

Your Signature Is the North Star.

Your signature (under Fed. R. Civ. P. 11 or state analogues like NY Part 130) remains the ultimate certification. AI does not dilute that responsibility. State plainly: every assertion of fact and law must be personally verified by a human lawyer before filing. Full stop.Mandate Secure, Enterprise-Grade Tools.

Explicitly forbid using consumer chatbots for client-confidential facts or strategy unless you have informed client consent and a confidentiality arrangement that bars provider access/use. If you absolutely must use a consumer chatbot (e.g. the $20/month ChatGPT offering), make sure you have disabled training on your data. Default to enterprise/API tiers with contractual no-training commitments, encryption at rest and in transit, and auditability. Run the same third-party risk diligence you use for any system touching client data.Training and Records Are Not Optional.

A policy is useless if it lives in a binder. Train lawyers and staff on what the policy is, why it exists, and how to use approved tools safely (e.g., redaction, test datasets, prompt hygiene). Establish retention/preservation practices for prompts and outputs. Build a pre-filing checklist that includes: (a) local-rule and judge-order review for AI disclosures; (b) verification of all citations and quotes; (c) confirmation that the correct (enterprise) workspace and privacy controls were used.

Ultimately, courts don’t care what tool a lawyer used. They care about the integrity of what’s filed. Building a rigorous, human-centric verification process around a secure AI tool isn’t just about avoiding sanctions. It’s about honoring the duties of competence and confidentiality that define the profession. The firms that get this right won’t just be safer; they’ll be better at serving their clients.

Moving Forward with Confidence

The path to responsible AI adoption doesn't have to be complicated. After presenting to nearly 1,000 firms on AI, I've seen that success comes down to having the right framework, choosing the right tools, and ensuring your team knows how to use them effectively.

The landscape is changing quickly - new capabilities emerge monthly, and the gap between firms that have mastered AI and those still hesitating continues to widen. But with proper policies, the right technology stack, and effective training, firms are discovering that AI can be both safe and transformative for their practice.

Resources to help you get started:

If you'd like a copy of my 50-state AI compliance research, just send me a note. I also work directly with firms to identify the best AI tools for their specific needs, develop customized implementation strategies, and, critically, train their teams to extract maximum value from these technologies. It's not enough to have the tools; your people need to know how to leverage them effectively.

For ongoing insights on AI best practices, real-world use cases, and emerging capabilities across industries, consider subscribing to my newsletter. While I often focus on legal applications, the broader AI landscape offers lessons that benefit everyone. And if you'd like to discuss your firm's specific situation, I'm always happy to connect.

Contact: steve@intelligencebyintent.com

Share this article with colleagues who are navigating these same questions.