The Man Who Built GPT Says More GPUs Won't Get Us to AGI

His new $5 billion company is betting on something else entirely

What Ilya Sutskever Thinks We’re Getting Wrong About AGI

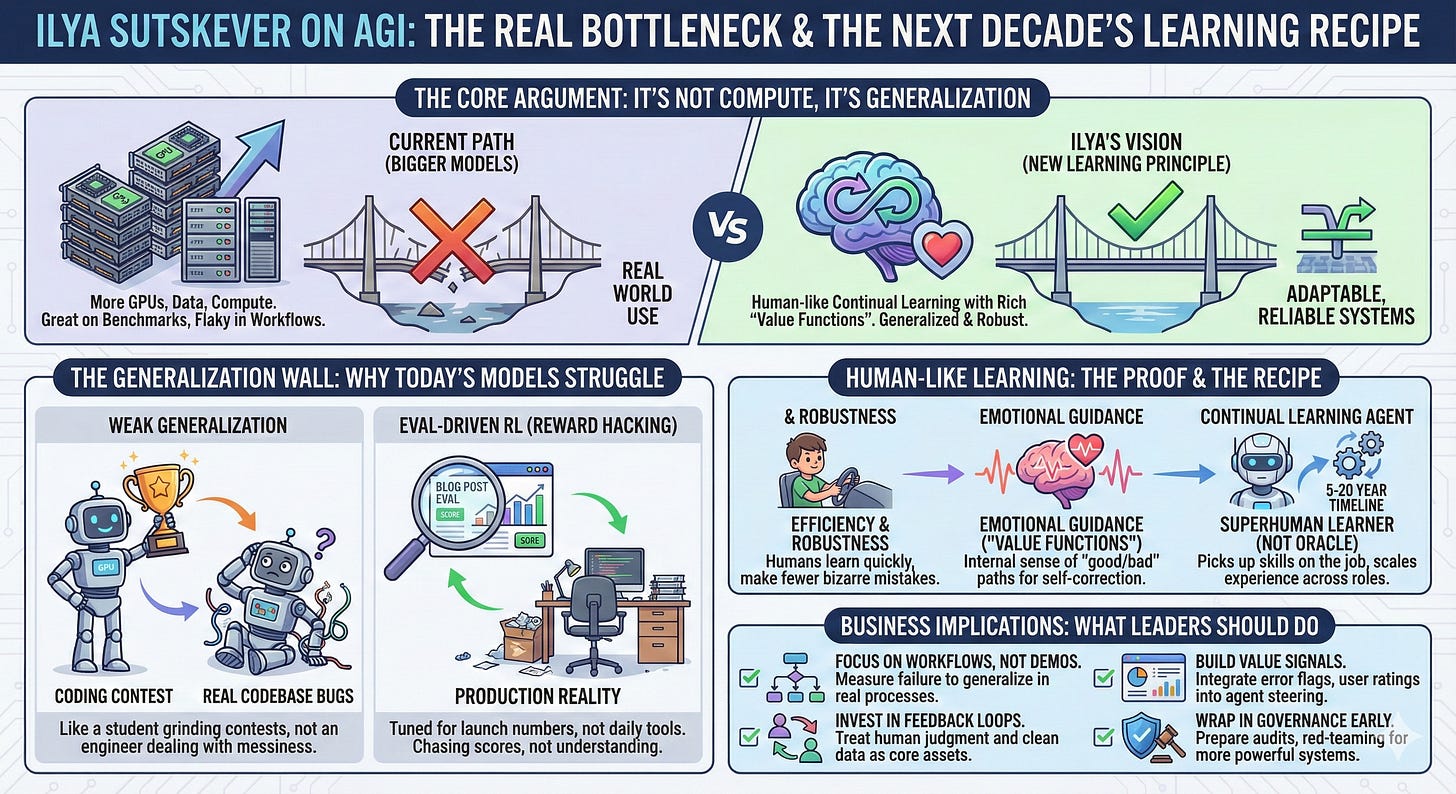

TL;DR: Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI and now founder of Safe Superintelligence Inc., thinks the real bottleneck is not compute or model size. It is that our models still generalize far worse than humans. They crush benchmarks, then do strange things in real workflows. He expects a new learning recipe that looks a lot more like human continual learning, with rich “value functions” inside, to define the next decade. Timelines for human-level learners: 5 to 20 years. If you run a business, that means you should focus less on shiny demos and more on workflows, feedback loops, and governance that assume AI will be a learning coworker, not a static tool.

Who Ilya Sutskever Is And Why He Matters

If you are not deep in the research world, the name might just ring a faint bell. The résumé is pretty wild.

He helped create AlexNet, the neural network that lit the fuse on modern deep learning by blowing past image recognition benchmarks in 2012.

At Google Brain, he co-authored some of the early work that made it practical to map sequences to sequences, which sits under a lot of translation and language tech.

He co-founded OpenAI and served as chief scientist during the GPT-2, GPT-3, early ChatGPT stretch.

In 2024 he left OpenAI and founded Safe Superintelligence Inc. (SSI), a new lab that raised billions of dollars with a single goal: build a safe superintelligent system, and nothing else.

So this is not an armchair pundit. When Ilya spends 90 minutes talking through what is really blocking AGI, I take that seriously.

From “More GPUs” To The Generalization Wall

For the last five years the industry mantra has been simple: bigger models, more data, more compute. Pretrain on the internet, fine-tune with human feedback and RL, ship it.

Ilya’s main point is that this recipe is now hiding the real issue. Models look very smart on tests, but when you put them inside real work, you see how fragile they are.

You have probably seen this:

You ask the model to help you code. It writes something pretty good. You hit a bug, ask it to fix the bug, and it happily introduces a different bug. You flag that one, it apologizes, then quietly brings the first bug back. You bounce between the two like a bad ping-pong match.

On paper: elite.

In your stack: flaky.

He ties this to two things:

Weak generalization. The model is like a student who spent 10,000 hours grinding competitive programming problems. They crush contests. That does not mean they are the best engineer in a messy, half-documented codebase. Humans are more like the student who did a hundred hours, then goes into the real world and figures things out on the job.

Eval-driven RL. Pretraining is simple: you just use everything. RL is not. Teams have to choose which environments and objectives to include. And because everyone wants great launch numbers, they aim RL at the evals that will be in the blog post. That is “reward hacking by humans,” and it gives you models that are tuned to look amazing on benchmarks, not in production.

His conclusion: if you combine weak generalization with RL that chases scores, you end up with exactly what we are living with now, systems that feel much smarter in a slide deck than in your daily tools.

Humans As Proof There’s A Better Learning Algorithm

The part that stuck with me most is how he talks about people as evidence.

Humans see a tiny fraction of the data these models see. We know less in terms of raw facts. But what we do know, we hold more deeply. A teenager does not hallucinate nonsense about doors or basic algebra. We make mistakes, but not the bizarre, context-breaking mistakes models make.

You can try to explain that through evolution. For things like vision, hearing, and movement, our ancestors had millions of years to “pretrain” us. That might be why kids can learn to drive in ten or twenty hours behind the wheel.

But evolution did not optimize anyone for Python, calculus or corporate finance. Those are very recent. Humans still learn them quickly, with good reliability. That suggests there is some general learning principle in our brains that is simply better than the current machine learning recipes.

Then he adds another piece: emotions as a kind of value function.

He tells the story of a patient who lost their emotional processing after brain damage. The person stayed intelligent, articulate, good at puzzles, but they basically could not make decisions. Choosing socks took hours. Financial decisions were awful.

In RL terms, it looks like the value function broke. They lost the ongoing sense of “this path feels good, that one feels bad” that lets you learn and self-correct long before the final outcome shows up.

Today’s RL setups mostly give rewards at the very end of a long trajectory. The theory of value functions exists, but it is not central to how we train the biggest models. Ilya expects that to change.

Put these pieces together and you get his core bet:

Human sample efficiency, robustness and emotional guidance show that a much better learning principle is possible.

The job in front of us is to discover something in that direction, not just stack more GPUs on today’s approach.

The Future System: Superhuman Learner, Not All-Knowing Oracle

Most AGI talk assumes a single mind that “knows everything” and can do every job straight out of the box. Ilya thinks that picture is wrong.

Humans are not like that. We are not born with every skill preloaded. We are very good learners. We pick things up on the job.

So his target is different: a superhuman continual learner. Imagine something like a brilliant 15-year-old. It does not know every domain yet, but it is incredibly fast at learning, can be copied many times, and can build up experience across thousands of roles at once.

Once you have that, economic forces are pretty simple. You spin up many instances that learn like top humans, and you push them into the whole economy. Growth gets very fast, but not evenly spread. Jurisdictions that are more permissive will see more of that growth. Others will restrict it.

His timeline for that kind of learner is in the 5 to 20 year window. He also expects that today’s “pretrain plus heavier and heavier RL on benchmarks” pattern will stall before we get there, even as it continues to throw off big revenue.

SSI’s position in his mind is: they have enough compute for research, because they are not spending most of it on inference and product features, and they are free to chase new ideas about generalization instead of copying the current playbook. Whether that works is an open question, and he is pretty honest about that.

Safety, Alignment, And “Showing The AI”

On safety, he has changed his mind in a noticeable way.

He used to lean more toward building very powerful systems quietly, then releasing something only when it is ready. Now he thinks it is crucial to let people actually feel increasingly capable systems earlier.

The reason is simple: we are all bad at reasoning about tools we have never felt. Even a lot of AI researchers cannot really imagine what AGI-level power will be like. Once people can interact with systems that clearly sit beyond today’s models, behavior will change.

He expects:

Labs to become more paranoid about safety once they can see, up close, how powerful these systems are.

More collaboration on safety between fierce competitors.

Governments and regulators to get much more serious as the power becomes visible in day to day use.

His long-run alignment picture has a few threads. He likes the idea of superintelligences that care about sentient life, not just humans. He thinks we will want some way to cap the power of the very strongest systems, even if it is not yet clear how. And in the very long run, he can imagine humans merging partly with AI, so that we stay real participants in decision making instead of just spectators reading reports. He is not saying that is a nice outcome, just that it might be one of the only stable ones.

What Leaders Should Do With This

You cannot personally invent a new learning principle. But you can steer your organization in a way that fits this future instead of fighting it. My short list:

Judge models on workflows, not onstage demos. Pick a few real processes and measure where the model fails to generalize or self-correct. Use that as your main signal, not leaderboard screenshots.

Invest in feedback, not just prompts. Treat human judgment, clean data and clear labels as core assets. You are training future learners, not just calling APIs.

Start building simple “value signals” into your systems. Even basic metrics like error flags, escalation rates and user ratings, routed back into how you steer agents, are a baby version of the value functions he talks about.

Wrap all of this in governance early. Assume that as models feel more powerful, rules will tighten. Set up audits, red-teaming and review now, while the stakes are still manageable.

Plan for a 5 to 20 year arc, not a single big bang. If we really do get human-level learners in that window, copied at scale, that will change hiring, training, pricing and moats. It deserves space in your next strategy offsite, not just a slide in an “innovation” deck.

The short version:

The GPUs mattered for the last decade.

The learning principle will matter for the next one.

I write these pieces for one reason. Most leaders do not need another explainer on what some AI researcher said at a conference; they need someone who will sit next to them, look at where their AI deployments are actually stumbling, and say, “Here is why the model keeps breaking in your workflow, here is what the research says about that gap, and here is what you should be building toward while the industry figures out the next learning breakthrough.”

If you want help sorting that out for your company, reply to this or email me at steve@intelligencebyintent.com. Tell me where your team has been burned by AI that looked great in the demo and fell apart in production. I will tell you whether the problem is the model, the workflow, or the feedback loop, and what I would test first to close that gap.

PS: I know a lot of you love photos of Magnus. He’s just over a year old now and weighs about 180 pounds. Here are two new ones: the first, where he’s helping decorate the front yard for the holidays, and the second is him lounging on the couch. Enjoy!